Space Scandals in Philately

April 28, 2021

Views : 9111

It all started with the Russian dog, Chernushka. In March 1961, she “carried a prohibited item” on board the spaceship. The Soviet aviation doctor, Abram Moiseevich Genin, made a bet with his colleagues whether his wristwatch would work in zero gravity or not. So, he secretly sewed his watch to the blanket he put on the dog. Of course, after such an "experiment", all its participants, except Chernushka, received a strict reprimand from the management.

Surprisingly, but... all this has something to do... with the philately!

In 1960, when NASA was preparing for the “Mercury” project, they decided to send the first letter to space. However, astronaut John Glenn refused to take it. He even wrote on the envelope: "Sorry, we don't take the mail. J. Glenn".

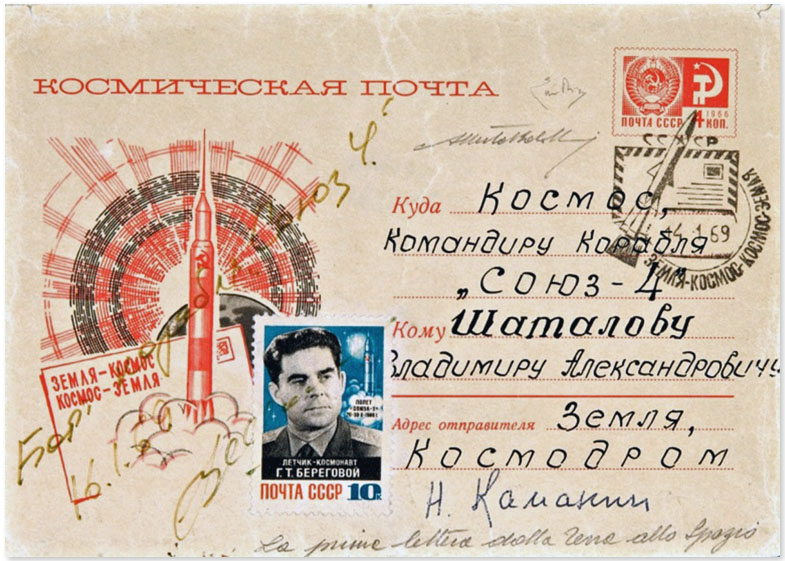

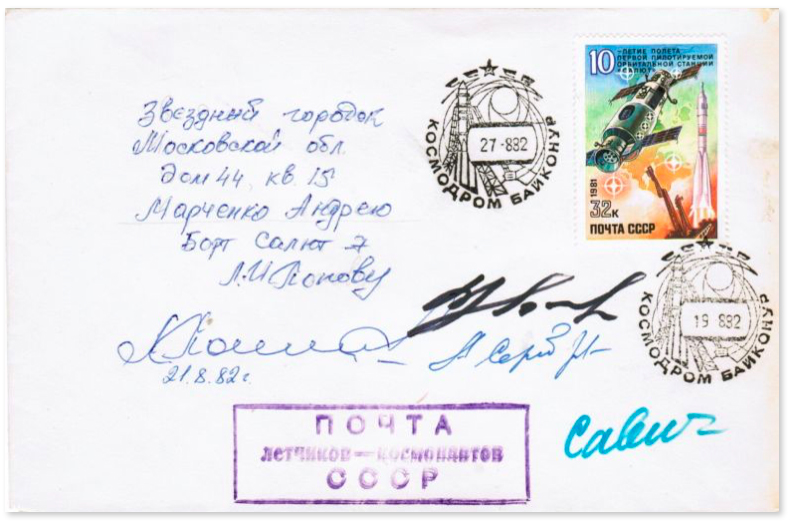

In their turn, the Soviet cosmonauts were more open to new ideas. 1969 was the year when astrophilately started after the Soyuz-4 and Soyuz-5 spacecraft docked. Vladimir Shatalov received the world's first space mail. It was a letter addressed to him from General Nikolai Kamanin. On the envelope, in the address bar, it was written: «Space. To Soyuz-4 commander, Shatalov V. A." For this purpose, a special envelope was made with a standard stamp "Space mail". The envelope was stamped “Earth-Space-Earth”. The letter, marked by Shatalov, returned to Earth later.

So, here goes a reasonable question: How did they manage to get the envelopes on board? Well, let's get it straight…

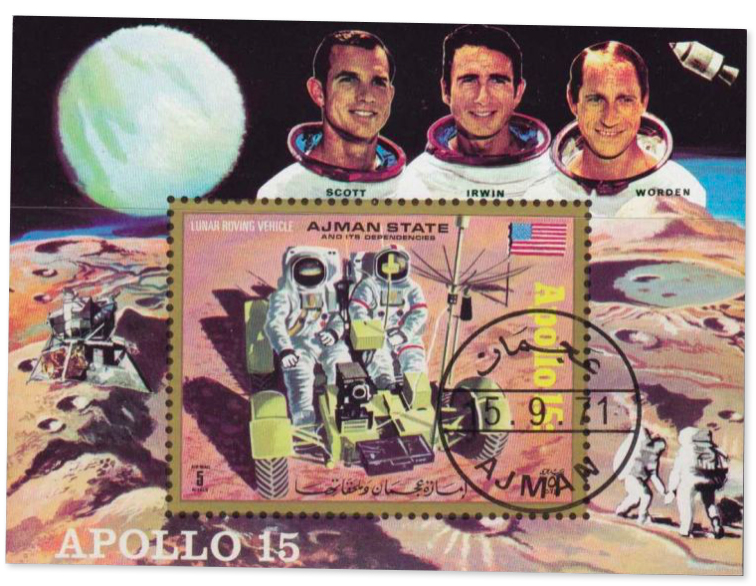

There were four astronauts who took part in this "philately fraud of the century" - David Scott, James Irwin, Alfred Wardin, and their friend Horst Eiermann.

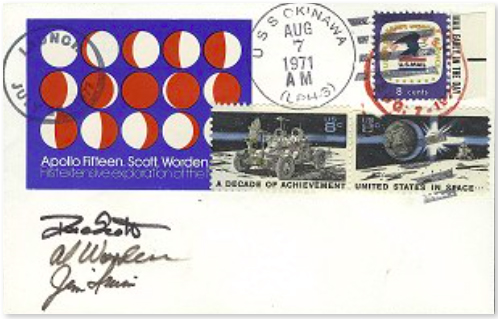

Scott ordered the envelopes to be stamped on the morning of July 26, 1971, the day of the Apollo 15 launch. The envelopes were packed and delivered to him. He brought them on board in the pocket of his spacesuit. Of course, they were not listed in his personal belongings. The envelopes spent their time on the Moon from July 30 to August 2. On August 7, the day they returned to Earth, they have stamped again on the rescue aircraft carrier, USS Okinawa. 100 envelopes were sent to Eiermann, who later passed them to Sieger, and the remaining envelopes were divided among the astronauts.

By the way, Warden officially brought on board 144 envelopes. In total, there were 640 envelopes on Apollo 15.

In June 1972, the US newspapers published the “Sieger Case”. It divided American society in half. Some believed the astronauts should not be allowed to make personal profits from NASA missions. Others didn't see anything wrong with it.

By 1977, all three ex-astronauts had left NASA.

In 1983, Warden sued and returned the envelopes. One of which was sold in 2014 for $ 50,000.

So, the astrophilately era started along with the space era. The United States and the Soviet Union have issued commemorative postage stamps with spaceships and satellites. Astrophilately was on top during the period when astronauts were landing on the Moon. Collectors were looking for philatelic souvenirs related to the American space flight program. Even astronauts often took part in their creation.

But let’s get back to Apollo 15.

In 1969, Eiermann met a stamp salesman named Hermann Sieger. This fateful meeting occurred by chance. They met on the bus on their way to the test site to watch the Apollo 12 launch. They started talking and it turned out both of them originated from the same region of Germany. Eiermann invited Sieger to his home. When Sieger learned Apollo 12 astronauts had brought a Bible with them, he came up with the idea of envelopes. So, he offered to persuade the Apollo team to take envelopes to the Moon, saying the money from their sale would go to the children of astronauts.

At the time, Eiermann was living in Cocoa Beach, Florida. He was a local representative for the Los Angeles-based “Dyna-Therm” Corporation which was a NASA contractor. According to Eiermann's published biography, a few months before the launch, his friend, Dick Slayton, invited Scott and other crew members to dinner at Eiermann's house.

There, Eiermann suggested the astronauts take envelopes with them on board. Later, in the midst of the scandal, during interrogations, Warden admitted he and Irwin, who had not previously gone into space, we're sure this was a common practice and did not suspect anything wrong.

Warden also said the astronauts were told the envelopes would not be sold until the Apollo program ended. And then they'd get $7,000 each. They were also told other Apollo crews had made the same agreements and profited from them. The astronauts agreed to the deal. At the time, Scott was earning $ 2,199 a month ($13,000 for 2020), Warden - $1,715, and Irwin - $2,235.

According to Scott, the astronauts also decided the envelopes would be a good gift, and requested 100 copies extra, which made a total of 400 pieces.

In his testimony, he thought the envelopes would be "a very private and non-profit thing". He added: "I accept I was wrong. I understand it now. But at the time, for some naive and thoughtless reason, I didn't understand the real meaning of it".

Irwin wrote in his autobiography the first meeting with Eiermann took place in May 1971, and the astronauts met him twice after that. Eiermann passed on Sieger's instructions on how to prepare the envelopes: they had to be stamped twice on the KSC: on the launch day and on the landing day. There was also supposed to be a signed application from the astronauts with a notarized authenticity certificate. Supposedly, the certification would make the envelopes more expensive.

In 1972, in his testimony before a Senate Committee, Qarden described Herrick as “a friend with whom he had past dealings” and with whom “he discussed the possibility of creating commemorative envelopes”. In 1972, according to the Justice Department report, before the Apollo 15 mission, Herrick told Warden that going to the Moon would be a smart investment because it would be a valuable thing for stamp collectors.

Herrick employed a commercial artist, Vance Johnson, with whom Warden discussed the design, and created 100 envelopes with the Moon phases. Warden listed them in his personal kit as “part of his personal belongings”. The crew bought several hundred dime issues of the First Man on the Moon postage stamps. They were glued to the envelopes with the secretaries from the astronaut's office.

The post office opened at 1:00 am. After the envelopes were passed through the blanking machine, they were taken to the astronauts' cabin, where members of the flight crew's support team sealed them in the Teflon-coated fiberglass to ensure they would be fire-resistant during the space flight.

Normally, the flight crew support team should have found this item was not on the astronaut's personal list. So, they would add it and make sure it was approved. But this time, the team leader claimed he had confused 400 envelopes with the Herrick envelopes approved by Slayton. When the mission was on its way to the Moon, 400 envelopes were moved to the lander craft. During the flight, the envelopes were signed by the three astronauts and so were Herrick's envelopes. Irwin recalled the signing took several hours.

On August 31, 1971, a notary in Houston printed certificates, stating that the envelopes were actually signed on the Moon. The envelopes had already been written by Scott and Irwin that they had landed on the Moon on July 30th. After the notarization, the last of Sieger's requirements for the envelopes was fulfilled.

Sieger notified his customers of the delivered envelopes and started selling them for 4,850 German marks (about $1,500 at the time) at a discount for those who bought more than one. He numbered and signed the back of the envelopes in the lower-left corner as a sign of their authenticity.

In November 1971, the Apollo 15 astronauts received and filled out the documents required to open accounts in one of the Stuttgart banks to receive agreed-on payments of $7,000. According to Scott's testimony, when they were in Europe, they heard Sieger started selling envelopes. Scott called Eiermann, who promised to investigate.

The discussion of the envelopes in the European philatelic publications alerted collectors in the United States. On March 11, 1972, Lester Vinick, the President of the Space Stamp and Envelope Collectors Research Group, sent a letter to NASA's chief legal counsel asking a number of questions about Zieger's envelopes. The information leaked to the media and in mid-July, everyone already knew about it.

None of the Apollo 15 crew ever flew into space again. They were reprimanded and fired, and they would never be promoted to the air force again. But they were offered other positions at NASA where their skills could be used.

Scott had been appointed as a technical consultant for the Apollo-Soyuz test project (the first joint mission with the Soviet Union) and retired from the air force in 1975. He became the Director of NASA's Dryden flight research Center, finally retiring from NASA in October 1977.

Warden moved to NASA's Ames Research center in California, where he remained until his retirement in 1975. Irwin retired from NASA in 1972 and founded an Evangelical group.

Surprisingly, but... all this has something to do... with the philately!

In 1960, when NASA was preparing for the “Mercury” project, they decided to send the first letter to space. However, astronaut John Glenn refused to take it. He even wrote on the envelope: "Sorry, we don't take the mail. J. Glenn".

In their turn, the Soviet cosmonauts were more open to new ideas. 1969 was the year when astrophilately started after the Soyuz-4 and Soyuz-5 spacecraft docked. Vladimir Shatalov received the world's first space mail. It was a letter addressed to him from General Nikolai Kamanin. On the envelope, in the address bar, it was written: «Space. To Soyuz-4 commander, Shatalov V. A." For this purpose, a special envelope was made with a standard stamp "Space mail". The envelope was stamped “Earth-Space-Earth”. The letter, marked by Shatalov, returned to Earth later.

However, there happened some scandals related to this specific philately branch.

The largest and most famous one involved the Apollo 15 crew. NASA put a life ban on them. The crew members coped with their task perfectly, but they decided to earn extra money by taking 400 gift envelopes on board, without NASA's knowledge. They were planning to sell them after returning to Earth.

So, here goes a reasonable question: How did they manage to get the envelopes on board? Well, let's get it straight…

There were four astronauts who took part in this "philately fraud of the century" - David Scott, James Irwin, Alfred Wardin, and their friend Horst Eiermann.

Scott ordered the envelopes to be stamped on the morning of July 26, 1971, the day of the Apollo 15 launch. The envelopes were packed and delivered to him. He brought them on board in the pocket of his spacesuit. Of course, they were not listed in his personal belongings. The envelopes spent their time on the Moon from July 30 to August 2. On August 7, the day they returned to Earth, they have stamped again on the rescue aircraft carrier, USS Okinawa. 100 envelopes were sent to Eiermann, who later passed them to Sieger, and the remaining envelopes were divided among the astronauts.

By the way, Warden officially brought on board 144 envelopes. In total, there were 640 envelopes on Apollo 15.

In June 1972, the US newspapers published the “Sieger Case”. It divided American society in half. Some believed the astronauts should not be allowed to make personal profits from NASA missions. Others didn't see anything wrong with it.

By 1977, all three ex-astronauts had left NASA.

In 1983, Warden sued and returned the envelopes. One of which was sold in 2014 for $ 50,000.

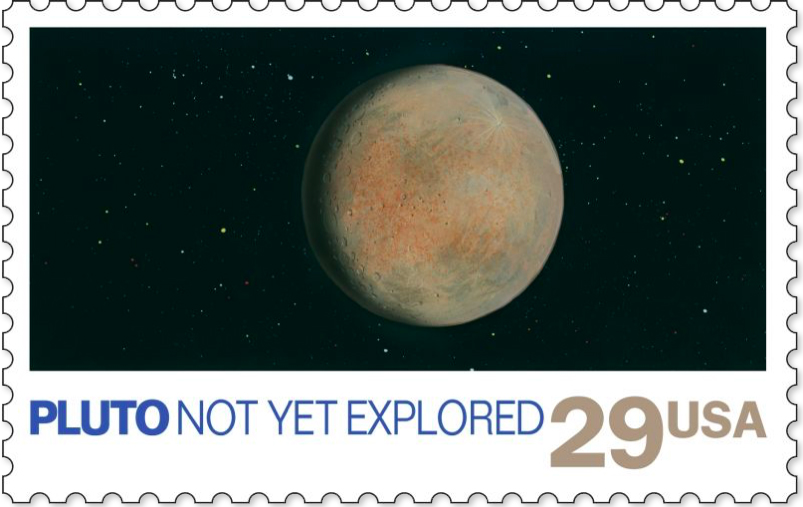

So, the astrophilately era started along with the space era. The United States and the Soviet Union have issued commemorative postage stamps with spaceships and satellites. Astrophilately was on top during the period when astronauts were landing on the Moon. Collectors were looking for philatelic souvenirs related to the American space flight program. Even astronauts often took part in their creation.

But let’s get back to Apollo 15.

In 1969, Eiermann met a stamp salesman named Hermann Sieger. This fateful meeting occurred by chance. They met on the bus on their way to the test site to watch the Apollo 12 launch. They started talking and it turned out both of them originated from the same region of Germany. Eiermann invited Sieger to his home. When Sieger learned Apollo 12 astronauts had brought a Bible with them, he came up with the idea of envelopes. So, he offered to persuade the Apollo team to take envelopes to the Moon, saying the money from their sale would go to the children of astronauts.

At the time, Eiermann was living in Cocoa Beach, Florida. He was a local representative for the Los Angeles-based “Dyna-Therm” Corporation which was a NASA contractor. According to Eiermann's published biography, a few months before the launch, his friend, Dick Slayton, invited Scott and other crew members to dinner at Eiermann's house.

There, Eiermann suggested the astronauts take envelopes with them on board. Later, in the midst of the scandal, during interrogations, Warden admitted he and Irwin, who had not previously gone into space, we're sure this was a common practice and did not suspect anything wrong.

Warden also said the astronauts were told the envelopes would not be sold until the Apollo program ended. And then they'd get $7,000 each. They were also told other Apollo crews had made the same agreements and profited from them. The astronauts agreed to the deal. At the time, Scott was earning $ 2,199 a month ($13,000 for 2020), Warden - $1,715, and Irwin - $2,235.

According to Scott, the astronauts also decided the envelopes would be a good gift, and requested 100 copies extra, which made a total of 400 pieces.

In his testimony, he thought the envelopes would be "a very private and non-profit thing". He added: "I accept I was wrong. I understand it now. But at the time, for some naive and thoughtless reason, I didn't understand the real meaning of it".

Irwin wrote in his autobiography the first meeting with Eiermann took place in May 1971, and the astronauts met him twice after that. Eiermann passed on Sieger's instructions on how to prepare the envelopes: they had to be stamped twice on the KSC: on the launch day and on the landing day. There was also supposed to be a signed application from the astronauts with a notarized authenticity certificate. Supposedly, the certification would make the envelopes more expensive.

In 1972, in his testimony before a Senate Committee, Qarden described Herrick as “a friend with whom he had past dealings” and with whom “he discussed the possibility of creating commemorative envelopes”. In 1972, according to the Justice Department report, before the Apollo 15 mission, Herrick told Warden that going to the Moon would be a smart investment because it would be a valuable thing for stamp collectors.

Herrick employed a commercial artist, Vance Johnson, with whom Warden discussed the design, and created 100 envelopes with the Moon phases. Warden listed them in his personal kit as “part of his personal belongings”. The crew bought several hundred dime issues of the First Man on the Moon postage stamps. They were glued to the envelopes with the secretaries from the astronaut's office.

The post office opened at 1:00 am. After the envelopes were passed through the blanking machine, they were taken to the astronauts' cabin, where members of the flight crew's support team sealed them in the Teflon-coated fiberglass to ensure they would be fire-resistant during the space flight.

Normally, the flight crew support team should have found this item was not on the astronaut's personal list. So, they would add it and make sure it was approved. But this time, the team leader claimed he had confused 400 envelopes with the Herrick envelopes approved by Slayton. When the mission was on its way to the Moon, 400 envelopes were moved to the lander craft. During the flight, the envelopes were signed by the three astronauts and so were Herrick's envelopes. Irwin recalled the signing took several hours.

On August 31, 1971, a notary in Houston printed certificates, stating that the envelopes were actually signed on the Moon. The envelopes had already been written by Scott and Irwin that they had landed on the Moon on July 30th. After the notarization, the last of Sieger's requirements for the envelopes was fulfilled.

Sieger notified his customers of the delivered envelopes and started selling them for 4,850 German marks (about $1,500 at the time) at a discount for those who bought more than one. He numbered and signed the back of the envelopes in the lower-left corner as a sign of their authenticity.

In November 1971, the Apollo 15 astronauts received and filled out the documents required to open accounts in one of the Stuttgart banks to receive agreed-on payments of $7,000. According to Scott's testimony, when they were in Europe, they heard Sieger started selling envelopes. Scott called Eiermann, who promised to investigate.

The discussion of the envelopes in the European philatelic publications alerted collectors in the United States. On March 11, 1972, Lester Vinick, the President of the Space Stamp and Envelope Collectors Research Group, sent a letter to NASA's chief legal counsel asking a number of questions about Zieger's envelopes. The information leaked to the media and in mid-July, everyone already knew about it.

None of the Apollo 15 crew ever flew into space again. They were reprimanded and fired, and they would never be promoted to the air force again. But they were offered other positions at NASA where their skills could be used.

Scott had been appointed as a technical consultant for the Apollo-Soyuz test project (the first joint mission with the Soviet Union) and retired from the air force in 1975. He became the Director of NASA's Dryden flight research Center, finally retiring from NASA in October 1977.

Warden moved to NASA's Ames Research center in California, where he remained until his retirement in 1975. Irwin retired from NASA in 1972 and founded an Evangelical group.